In the 1960s a deep canal was dug across the Venetian lagoon to give access to bigger ships to the commercial harbour at Marghera, and since then Venice has been flooded by ever more frequent and ever higher tides.

To counter this threat to Venice’s existence a system of mobile flood gates was devised at the three openings between the lagoon and the sea. They’re still being built. The costs are now over 6bn Euros, nobody knows if they will ever work, and the whole affair has become a cesspool of corruption and mismanagement of public funds.

Now, to make sure the next generation of still larger cruise ships will be able to enter the lagoon, a new branch of the canal from the 1960s will be made to take the 70m wide and 360m long future ships into Venice. The project is being sold as a necessity to avoid having the ships pass in front of St.Mark’s, without promising that they won’t, and as an environmental project to repair the massive damage caused by the first canal.

These are all lies. There is absolutely no doubt that this new canals will wreak havoc with the fragile ecosystem of the lagoon, already seriously compromised by the first canal, yet the government in Rome and their lackeys in Venice wants to force this new canal on a city that doesn’t want it.

The Canale dei Petroli

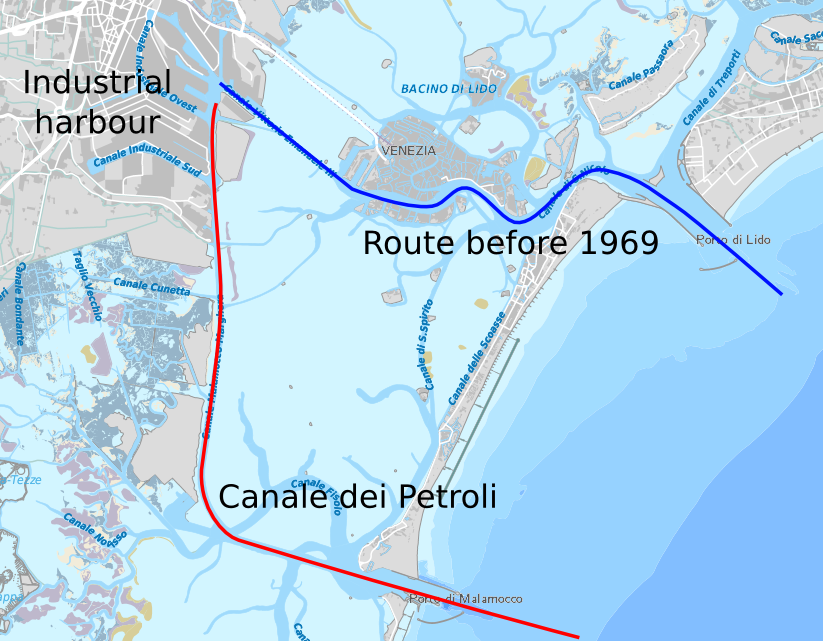

About a century ago, when the harbour in Venice city was no longer adequate for the traffic of the time, a new industrial harbour was built on the mainland at Marghera and a canal (called the Vittorio Emanuele) was dug to allow the still bigger ships to pass through Venice on to the new harbour behind the city.

In the 1950s traffic and ship sizes had reached a level where having them pass straight through the centre of Venice city was no longer viable, and a new canal was dug, the Canale dei Petroli, leading from a more southern opening to the sea at Malamocco/Alberoni about 15km south of Venice, straight across the lagoon and up north along the mainland to the industrial harbour at Marghera.

Two huge areas destined for further industrial expansion were created at the bend of the new canal, by filling up large tracts of lagoon. They’re called the casse di colmate, but much of this was never finished and the areas lie waste even now.

This new canal has all but destroyed the central lagoon where it starts, and it has made huge changes to the tidal characteristics of the southern lagoon.

Winding and bending shallow canals have been replaced by a 12m deep 100m wide canal which channels a massive amount of tidal water through the lagoon at full speed. The erosion has been enormous. The following three maps show the average water depth in the lagoon in the 1930s, in 1970 and in 2002 (darker blue is deeper).

Tens of millions of cubic metres of sediment has been lost to the sea over the last four decades.

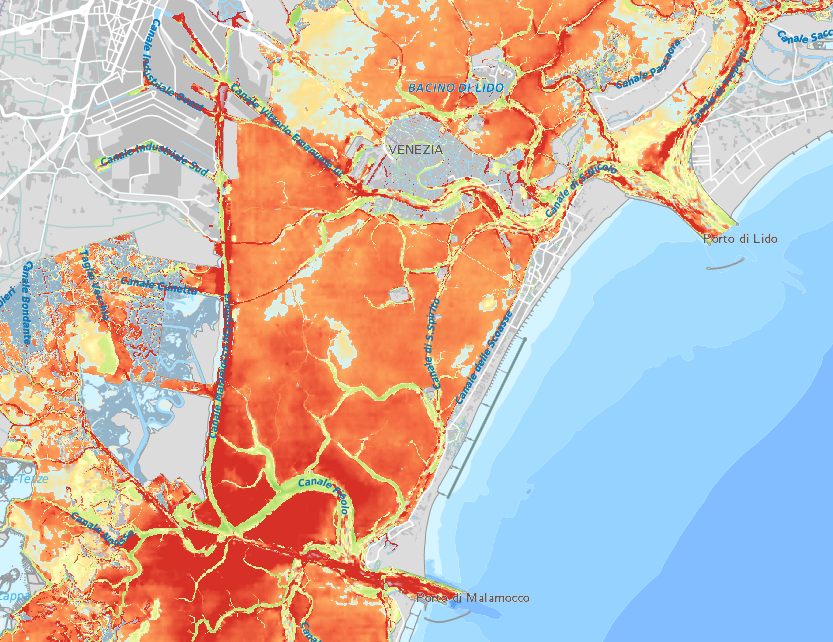

The map below summarises the changes in depth in the central lagoon over the period 1970 just after the digging of the Canale dei Petroli, and in 2002. Darker orange/red is deeper, green is shallower.

The entire area has become deeper, the most affected parts up to 2m deeper, except for the ancient natural canals which have silted up as less water now follows that path.

In short the bottom of the central lagoon has been levelled out by the tidal current through the new canal.

The tidal watershed

Besides having turned the central lagoon into a branch of the sea, now complete with flying fish and dolphins, the tidal flow through the canal have moved the tidal watershed in the lagoon.

A rising tide enters the lagoon through each of the three opening to the sea and in between there are two areas where the opposing tidal currents meet. At these tidal watersheds there is no current at any time, being the meeting point of two opposing currents.

Historically Venice has depended on the tide for cleaning the city canals. One could say that nature flushed their toilets twice a day, and the Venetians knew this and were always very careful to monitor the watershed whenever they made changes in the lagoon.

There was no such foresight when the Canale dei Petroli was dug.

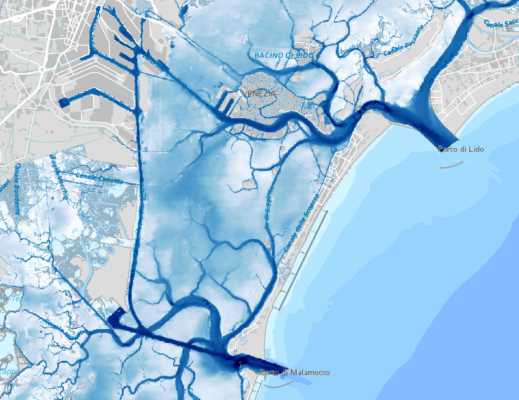

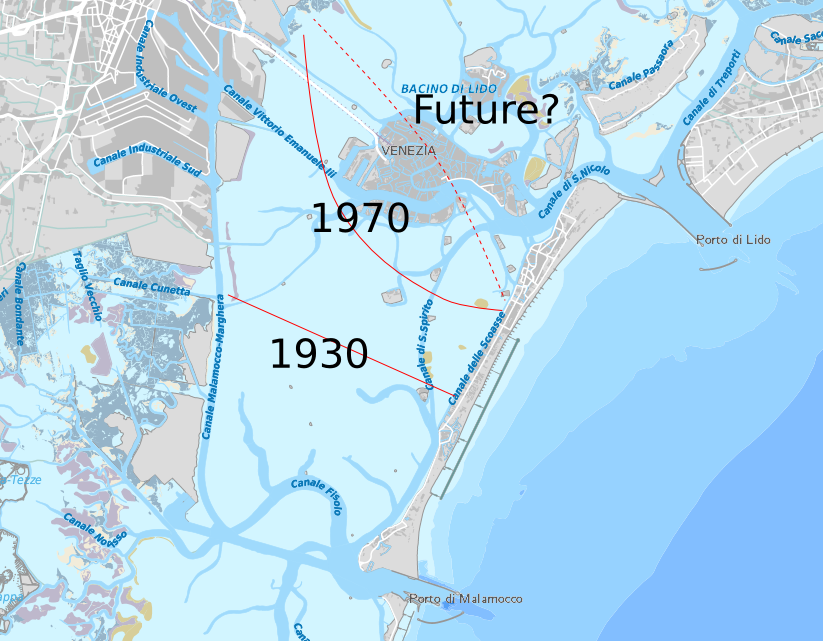

The tidal watershed in the central lagoon, where the tides from the San Nicolò passage and the Malamocco passage meet, has therefore moved, pushed north by the now larger volume of water entering at Malamocco having a wider and more direct passage.

It used to be roughly in the middle, but with the Canale dei Petroli the watershed was pushed up behind Venice, just outside the city.

The map below show where the tidal watersheds have been approximately, before the Canale dei Petroli, after the canal and if the new cruise ship canal is dug.

In short, the flushing effect of the tide has been very reduced since the digging of the Canale dei Petroli, and with the new canal planned it will be a thing of the past.

With the new Canale Contorta the water in most of Venice will be stagnant.

The frequency of high tides

Following the digging of the Canale dei Petroli Venice has suffered from ever more frequent high tides, as a consequence of the changes in the hydraulics of the lagoon.

The city administration has a tidal forecast office which also keeps detailed statistics of the tides, and their graphs are revealing.

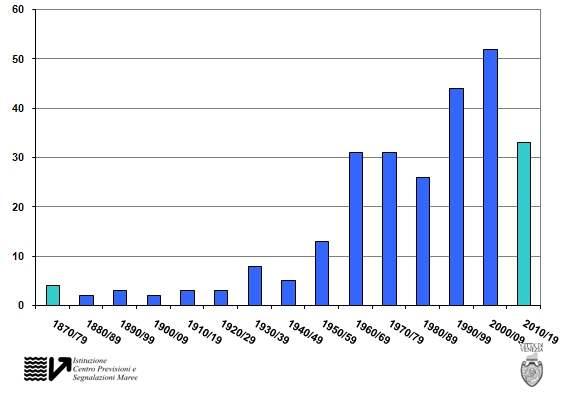

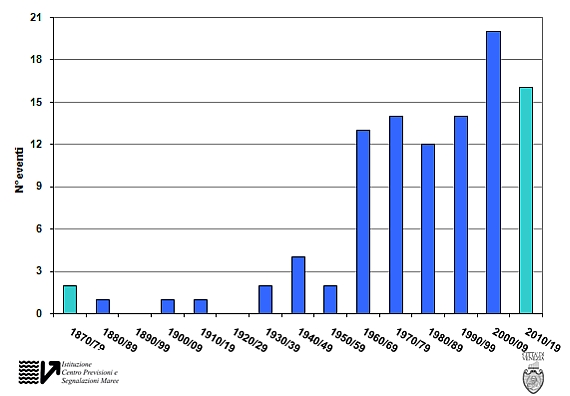

This is the frequency of tides over 110cm (which floods 12% of the city) aggregated over each decade since measurements were made.

The same graph for tides over 120cm which floods 28% of the city.

The conclusion is evident: mess with the lagoon and you mess with Venice.

The MOSE project

However, rather than trying to roll back the changes made, another technological fix was chosen.

The MOSE project is for a set of huge floodgates to be built at each of the three openings between the sea and the lagoon, at San Nicolò in the north closest to Venice, at Malamocco in the middle where the Canale dei Petroli starts, and in the south at Chioggia.

The gates will lie at the bottom filled with water when not in use, and when a tide of 110cm or more is predicted, they will be pumped full of compressed air and swing up on hinges to impede the water from rising.

A tidal level of 110cm is already problematic for the city, but if the flood gates are activated at a lower level, they will be closed so often as to compromise the entire lagoon as a tidal marsh. The ecosystem of the lagoon breathes with the tide, and it will morph into something else if the tide is removed.

The original project was expected to cost little over 1bn Euros, but costs have inflated repeatedly and the bill now stands at over 6bn Euros.

The flood gates are still not operational. That is expected to happen in 2017.

The whole project has become a cesspool of corruption and mismanagement of the public funds involved. Rumours speak of about a quarter of the entire cost non being accounted for, and arrests have been made in the leadership of the consortium of companies building the flood gates, and in the public offices supposed to supervise the construction, both at the level of the state and the various agencies involved, the region of Veneto and in the city of Venice.

Most of Venice has been opposed to the building of the flood gates, in part because of the still unknown environmental impact of the project, and in part because it has diverted all the funds Venice used to received from the state for protecting and maintaining the city.

As the situation is now, the flood gates are not operational, nobody knows if they’ll work and it is not clear what the final environmental impact of the gates will be. What is sure is that a lot of well connected people have become a lot wealthier with all the money they have managed to extract from the project.

Until now, all that has been done to stem the high tides flooding Venice has had no positive effect whatsoever.

Cruise ships in Venice

Cruises and ferries were the only harbour activities which remained in Venice after most commercial shipping moved to Marghera.

Lately the ferries have moved to the mainland too, leaving only the cruise ships. They have, however, taken a huge upswing.

An ever rising number of cruise ships enter the cruise harbour of Venice every year, up to 600-700 visits a year, with as much as 12 ships in the harbour at any one time.

The ships have also become ever larger. The current generation of cruise ships are over 300m long, 50m wide, 50m tall with a draught of 10-12m, and with a displacement of 140,000 tonnes. They carry up to 3500 passengers and a crew of 1500-2000.

These ships are flowing cities.

The Titanic in comparison was 40,000 tonnes and not even half the width of a modern cruise ship.

The next generation will be even more gigantic, measuring up to 360m in length and 70m in width, with a displacement of 200,000 tonnes. They will not be taller or have a larger draught, as that would prevent them from entering many of the harbours they’re working from. The only way to make the ships bigger is to make them longer and wider.

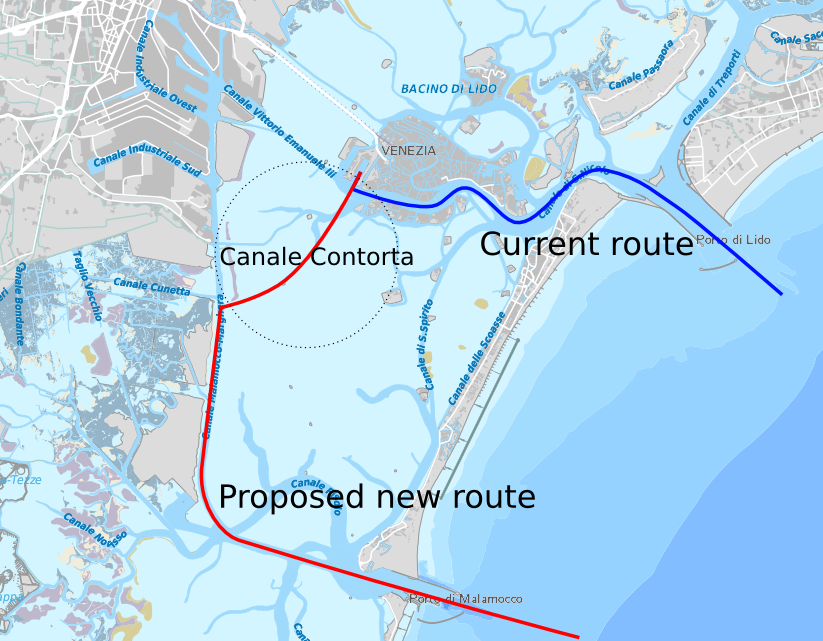

The current route followed by the cruise ships to the cruise terminal in Venice is marked in blue on the map below.

This huge cruise ships pass straight through the centre of the city, and to say the least they’re an eyesore.

Various measurements of the air quality indicate that each of these ships pollute like 15,000 cars. With up to 12 of these passing on a good summer’s day, its like living on the side of a very busy motorway.

The route from the sea to the cruise terminal is very narrow as only a part of the basin in front of St.Mark’s have the required depth for the cruise ships to pass. The tight passage and the many sharp turns are beyond the manoeuvrability of the ships, and they’re always accompanied by two tugs, one in front and one behind, to help them turn the corners. They’re not able to navigate the passage on their own.

It is very unlikely that the next generation of cruise ships, being 20% longer and wider, will be able to negotiate this passage.

The Canale Contorta or Caotorta

Hence the need for the powers that be to find another passage to the existing cruise terminal, which have received substantial investments in recent years.

The residents have helped a bit. There is a marked hostility in the city of Venice towards the cruise ships passing through the city centre. They are very very ugly, the pollution scares people and they bring very little if any economic benefit to the populace in general.

Even the association of hotel owners in Venice have stated that they’d rather be without the cruise tourists who generally spend very little in Venice as they both sleep and eat on board.

The harbour authority has for a long time had the project for another access way to the cruise terminal in their drawers. With the mounting pressure to remove the cruise ships from the centre of the city following the Costa Concordia disaster in Tuscany, the plan for the Canale Contorta was taken out again.

The plan is to make a branch on the Canale dei Petroli that will lead straight to Venice.

The Canale Contorta already exists and always have. It is about 15m wide and has a depth varying between less then 1m and about 2m. It can only be used by small boats and as all natural canals in the lagoon it is winding, not straight.

What the harbour authority proposes as a “recalibration” of the canal, will take it to 100m in width, over 10m in depth and straighten it out.

They’re taking a pretty country lane and making it into a motorway surrounded by mounds, calling it a “recalibration”.

The 6 million cubic metres of polluted mud they’ll have to dig away will be used to create what they call “marsh islands” around the canal. This is most likely to contain the waves caused by the displacement of the ships, and probably just as important, to dispose of the mud as close to digging site as possible to keep costs down. This is marketed as an environmental investment to return the central lagoon to what it was before the Canale dei Petroli was dug.

Other projects have been tabled, such as a new cruise terminal in Marghera as large parts of the old industrial harbour is unused and the canal already exists; or an off shore cruise terminal outside the MOSE flood gates at San Nicolò, but all alternatives have been swept away as inadequate, and only the Canale Contorta project has been examined.

This decision was taken by the government in Rome in mid August.

The project has to undergo a VIA, valutazione dell’impatto ambientale, or environmental impact assessment. This process should have taken two month including public debates, but the harbour authority has managed to fast track the procedure, claiming the project is of strategic national interest, so the VIA will be just 30 days and without any kind of public debate.

The residents of Venice has taken up the fight. They have collected almost 30,000 signatures online and around the city; and groups are contesting the project and the way it is forced through the system through legal means.

The impact of the canal will be to exacerbate the damages the Canal dei Petroli has already done to the lagoon, and mostly likely undo whatever positive effect the MOSE project might have on the lagoon in the future.

State versus city

How come such decisions are taken when the locals are clearly against them?

It is all a matter of state versus local administration.

The harbour of Venice is not the harbour of Venice city. It is a state harbour. The managers and directors are appointed in Rome, and they appoint people who share the government’s view of what should happen in the harbour.

Venice city and the local population has no say whatsoever in what the harbour authority does or doesn’t do.

What money the cruise industry brings to ‘Venice’ doesn’t benefit Venice city. All the money goes to Rome, to the government, the owner of the harbour.

When the Canale dei Petroli was build there probably wasn’t much of a public debate, but the MOSE project was fiercely contested locally. Yet the project was steam rolled over the city and local objections, channelling all funding from safeguarding the city to pouring cement in the lagoon.

As the mismanagement and corruption of the MOSE project has been revealed in the last few years, it has been clear that the opposition back then was right all the way, yet they were derided in the press, dragged to court and almost bankrupted, had their academic careers damaged.

Now the same procedure is repeating all over. Government agencies are forcing the project through against local opposition, and with all likelihood the canal will be dug, and with all likelihood the environmental damage will be massive and irreversible.

As an extra little finesse this time the powers that be have managed to force the mayor of Venice to resign after accusation of corruption related to the MOSE project, so the city of Venice has no democratically elected local government any more. The city is currently managed by a government appointed commissioner, who doesn’t speak up against the government in Rome, his employer.

That is Venice’s future if the Italian government gets it their way. In the process a lot of people will get richer and more powerful, and the mess they leave behind will be left to the future residents of Venice, who never wanted any of the projects from Rome.

The high tides will be ever higher and ever more frequent.

Leave a Reply